Scaling Test Teams

There’s a question that all “schools of thought” in software testing slip and sweep under the rug. Some of them do so by:

- A) acknowledging it and making rubbish back-of-the-envelope estimations turned into “worldwide enforceable standards” proclaimed by

for profitorganizations turned intofauxunited nations of testers (e.g. ISTQB)

while others

- B) disregard it and make blank statements of “it depends” and “to each their context, I shall not tell you. Thank you for coming to my TED talk, that will be 5000 euros.“…

I admit, both of these are exaggerated extremes, but both are visible whenever someone asks the question

How many Testers (or Test Engineers/Technical Testers) should my team have?

Folks either promote a ready-made final solution based on their own reality or their imagination, OR they understand that the question is heavily linked to one’s context and, not knowing the context, prefer to not induce folks to error with a final solution.

I risk saying: you won’t actually find many craftsman testers worried about this question, more often than not they are on the next stage of the problem: I already know what kind of testers I need and how many of them I need for my context, but I can’t get them, either due to lack of money or other compromises in my org.

BUT, for the rest of the world, this is a question that troubles non-Testing lay-people looking desperately for an answer, some of which will resource to a solution that is faith-based, money-based, family-based, witchcraft-based, … in sum, desperate folks looking for a solution prone to complete failure and being taken advantage of.

So, what is my “look here in my pocket” kind of solution that I propose instead for these desperate people?

Well… here it goes, I propose a balance:

between a back-of-the-envelope estimation and an understanding of underlying context.

This balance is an exercise, basically an heuristic, that in the recent years I used to do mentally but never put into words. Let me make up a name for it on the fly:

A node-weighted approach to scale Software Testing and Test Engineering Teams for the benefit of smart or dumb software development environments

Patent pending. Alright, fancy words done. What is it about and how can you use it?

I’ll try to explain it all in 3 steps:

- Understanding the Test/Test Engineering function.

- Understanding the weight of each branch and how it links with the overall function.

- Purging the system from non-useful weight, or, better put, keeping the system clean of bullshit.

Understanding the Test function

I’ve written about Testing and its importance on other posts in the past. In order to properly scale any testing related team you have to understand what the Testing function is. There are a couple core principles that I believe are crucial to get right from the start before doing any scaling work:

Testing and Test Engineering are different faces of the same coin. You

can’tshouldn’t have a coin with two heads or two tails.

From the above principle, it’s been helpful for me to keep the bellow definitions also as core principles:

- Testing: it’s the art and craft of finding and exposing meaningful problems through learning and willful/purposeful interaction with the product. None of that “assurance of quality” crap, that’s another ballpark with other goals.

- Test Engineering: it’s the art of creating and maintaining tools and scripts that either help the product being more testable, or help Testers find problems with the product.

I admit this is a narrow view of what these two functions are, but, the implicit and intimate understanding of these, in similar lines, is what makes or breaks someone designing and scaling a testing function in a project. Too soon some folks setup teams and start hiring for positions not understanding the actual needs of a project, the function of Test, and what Testing really is. Other people in the org are drugged with wrongful principles and definitions, and what should be a simple exercise of defining the size of the Test function in a project, becomes a hazing exercise of “who’s got the biggest “quality assurance” Willy and influential power”.

From the above three principles you sketch out everything else:

- If your project needs folks who dwell in both crafts or a single craft;

- If you need someone specialized in a single craft;

- If you need someone specialized in a specific topic within being expert in one craft;

- How much is the market charging for any of the above;

- Knowing the market price, how many folks you’re able to pay/afford versus what your project needs;

- …

Understanding how the weight of each branch is linked with context

If you start doing a sketch of what you need versus what you might afford in different organizations you’ll soon observe a couple of points:

- The principles remain the same between different organizations, BUT, some organizations hold wrongful or other contradicting principles at the same time;

- The context of the org and projects plays a massive role in your sketch;

- The sketch for a small team is different than the sketch for a massive corporate context;

- What often determines the success in the long run of your final sketch is the weight attributed to each part of the whole Test function.

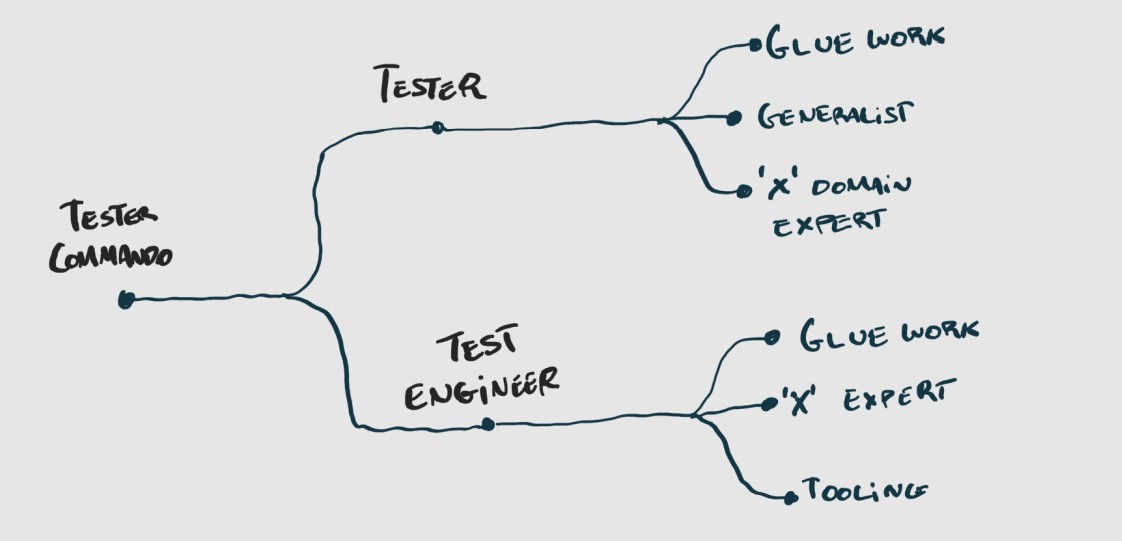

Let’s try to put this in a diagram:

Given a project of a certain scale, you’ll find yourself in the position of needing one or more of the following:

- Tester Commandos: folks that are seasoned Testers and Test Engineers, and skillfully improvise in any hardcore situation of the whole Test function.

Past a certain scale, when the project needs more stability and long-term vision on the Test Function than improvising on the job:

- You’ll likely need to split the “commando” role into folks that are foccused on either Testing or Test engineering specific functions.

And finally at a massive scale (which doesn’t always necessarily mean more complexity) you’ll want to branch out further into folks that:

- Play the “Glue” part, the kind of folks that first, mentor and grow other testers, guiding folks towards major goals, and act like a single acessible interface of the Test/Test Engineering team for the rest of the org. Not that any Tester can’t or should not interface with others, that is always part of the job, but oftentimes you need someone that represents “the whole”.

- Play the “Generalist” part, folks that do everything, a couple of things well, and the remainder well enough, but you don’t mind in balancing out each others strengths and weaknesses to establish a good Test team.

- Play the “Domain Expert” or “Expert” roles, meaning every tester or test engineer that doe a bit of everything on demand, but that you rely on for moments when true expertise in the product or on a kind of testing/tooling is required. As an example: think of an Expert Tester that knows all about Chaos, Systems Thinking and Dinosaurs working on a Live Dinosaur Theme Park, or think of an Expert Test Engineer that will quickly setup an appropriate Load Testing “scaffold” or do penetration testing and other kinds of security related testing on systems. They certainly are able to accomplish most Testing challenges, but are expert at a subset of these.

- Play the “Tooling” part, the kind of folks that, like all of the others, performs in-deep experiential testing, but where they truly shine is coding away scripts and tools in sync with the Test team. The tricky part is: lots of folks in the market for test tooling can indeed code anything or put in place any tool, but the ones that add value are those that “do the dance” in sync with the Test team’s actual realistic needs.

- And other parts that are not in the diagram, but would be branching out of the ones already there.

We can mold the above to any of the common scenarios:

- your specific project might not be of a huge scale, but is complex enough that you need folks that dwell between Testing and Test Engineering craft based on needs of the project at any moment;

- your project might favour having testers that are not generalist testers, but are hardened in one specific product domain;

- you might not need one extra craftsman Tester if you already have a good team of those, but they could definitely use someone that would help them coding some tools or scripts, …;

- you already have test engineers that code, but you could use a Tester that dives easily into a complex product, and is skilled at hunting all sorts of meaningful bugs;

- you already have a fair amount of testers and test engineers, but you could really use someone that tests some specific tech, like someone that knows the ins and outs of a specific mobile stack, or some async messaging systems or do all sorts of stress tests to a certain kind of service, …;

- …

If you identify the different roles/parts that you would need in your context, knowing how many of each you would need is an exercise of:

- Determining what you are able to afford in practice

- Based on budget restrictions, pin-point “where is the fire”: where would one person cause the most impact for your investment

And lastly, the favorite part for folks behind “the budget”: you can definitely attach a (fair, or unfair) price-point of the human-hours cost to each node of the tree, and similarly assign a weight, adapted to your hiring market and to your project’s needs. After that, the question is no longer how many folks do I need, but how many can I afford, based on the price/weight, and that is something only you are empowered to answer, no matter how many ready-made “for X number of developers you should have Y number of testing folks” answers you might have lying around from “experts”.

Usually when it comes to hiring market decisions:

- Some tech orgs will opt for a strictly local approach, where your purchasing power is based on

fauxbeliefs of premium office experiences and local market power and “premium” relocation packages, following early 2000s style of hiring practices; - Other tech orgs, that live in something called the current real world, will opt for a global and full-remote approach, where folks only need a good combo: fast internet, a chair, a desk and a laptop, and can work from anywhere in the world;

- And you can always make use of “Testing sweatshops” for a “band-aid”/”duct-tape” way of solving scale issues; this almost always bites you back in the long run in some form, and I have to be honest, personally I only know of a handful of shops that are decent, in an ever expanding sea of hundreds of abusive Test sweatshops.

- …

As for project’s needs, if feel you are disconnected towards your org’s reality, there’s a couple of key indicators that might help:

- if your current Test team is burned out and has more than they can chew on - you likely need more people, or you are putting weight on the wrong node the tree, or not even putting weight on any node of the tree (e.g. folks wasting the better chunk of their time on non-Testing activities);

- if you can’t afford more people, don’t throw sand into your existing Test team’s eyes: either make the project more testable/bearable and/or reward your current Testers with more money and freedom (e.g. let them work remotely from wherever, enforce clear work/life boundaries so folks can have a life, …);

- …

Keeping the system clean

The final step of solving the “how to scale a Test/Test Engineering team” issue is one that is not related to pricing or attributing the right weight and focus to parts of the system, but it is a problem of keeping your Test function “lean and clean”. Too often folks try to solve the “Testing” chunk of their development process by adding to the system, but not by maintaining the system. Perhaps this is easier to explain with examples.

- Folks in the Test Engineering side of the Test function might be cripled with common anti-patterns;

- Sometimes you try and solve Test problems with increasing the number of “Generalist” testers when in fact you need “Domain Experts”, and vice-versa;

- There might be pre-existing issues with the “Glue” part of your tree: Test leads defining rules of engagement that have nothing to do with the intimate realities of each smaller test teams, or having a test lead when one is not needed, or having multiple test leads with no test teams to lead and no one to “line-manage”, or test leads messing with other test teams that are not their own, …

- Sometimes there’s a wrongful focus and double-down on “Tooling” or “Test Engineering”, when the project is actually lacking in having Testers interacting and deeply Testing the product;

- The scale and complexity of your project might not justify a large Test team, when you could in fact make use of a handful of Tester Commandos;

- The scale and complexity of your project no longer justify a short-term Tester Commando approach, and you need to branch out and assign longer-term focus and specific goals to folks, e.g. I need someone to double-down on Test Engineering side and someone who is a seasoned craftsman Tester but isn’t necessarily someone whom I expect to be coding scripts and tools anytime soon;

- There’s a complete disconnect in your org of what Test function actually is and what problems it should be trying to solve, like the case of orgs that are plagued with crusades on quality infotainment;

- And many more …

The gist of this being - before answering the question of “how many testers”, it’s useful to try to answer other questions like: what kind of value are we getting from our current approach, and where could we do better with the people we already have. Oftentimes, no matter how well you design your Test function, your org is restraining the Test function from doing its best work through other parts of the “development process” system being overlooked and swept under the rug.

TL;DR: If you’re not convinced, but you read this far, I have a gift. An exact dev-tester ratio that works every time, well kept by wizards of Testing: for every 5 developers, you should have 3 Testers. The logic behind this is that 8 humans are enough to feed an adult Allossaurus and a handful of Velociraptors each day, and it always scales efficiently assuming you can control your Dinosaur population, and they are all females. PS. Do not use frog DNA.

If you read this far, thank you. Feel free to reach out to me with comments, ideas, grammar errors, and suggestions via any of my social media. Until next time, stay safe, take care! If you are up for it, you can also buy me a coffee ☕